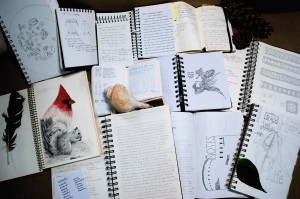

Not a journal or diary, not chronological or introspective, the commonplace book is akin to a scrapbook. It’s a way to condense and centralize any information of interest.

Observing and recording quotes, ideas, expressions, images, passages from books; segments from blogs, articles, essays; tables, charts, bits of conversation; whatever it might be that the compiler wants to refer back to or keep for possible future use is a natural for those involved in any creative activity.

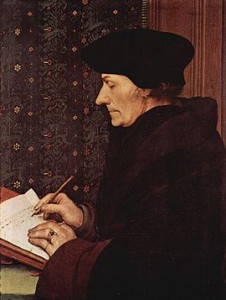

What’s old is new again. Begun in early modern Europe, commonplace books became a regular practice for scholars including John Locke and Francis Bacon. Part of university education, keeping commonplace books was taught at Oxford and Harvard. John Milton, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) all kept commonplace books.

Commonplace books can contain information on one subject or a variety of subjects, entered into the book as you come across them. I tend to keep one book until it’s full, then take up another. When working on a specific project, such as writing a new book, preparing a series of paintings, or learning a new subject, I try to keep all the information in a separate book just for that project. If the book isn’t at hand and I scribble notes for a project on a handy scrap of paper, I can add it to the book later on.

As a learning tool, record anything that is interesting or appealing in some way, to possibly use in future, or just for the pleasure of knowing it and being able to revisit or share it.

Maybe you prefer to keep your commonplace book online. That works too!

“Moonlight floods the whole sky from horizon to horizon.” -Rumi

“Moonlight floods the whole sky from horizon to horizon.” -Rumi

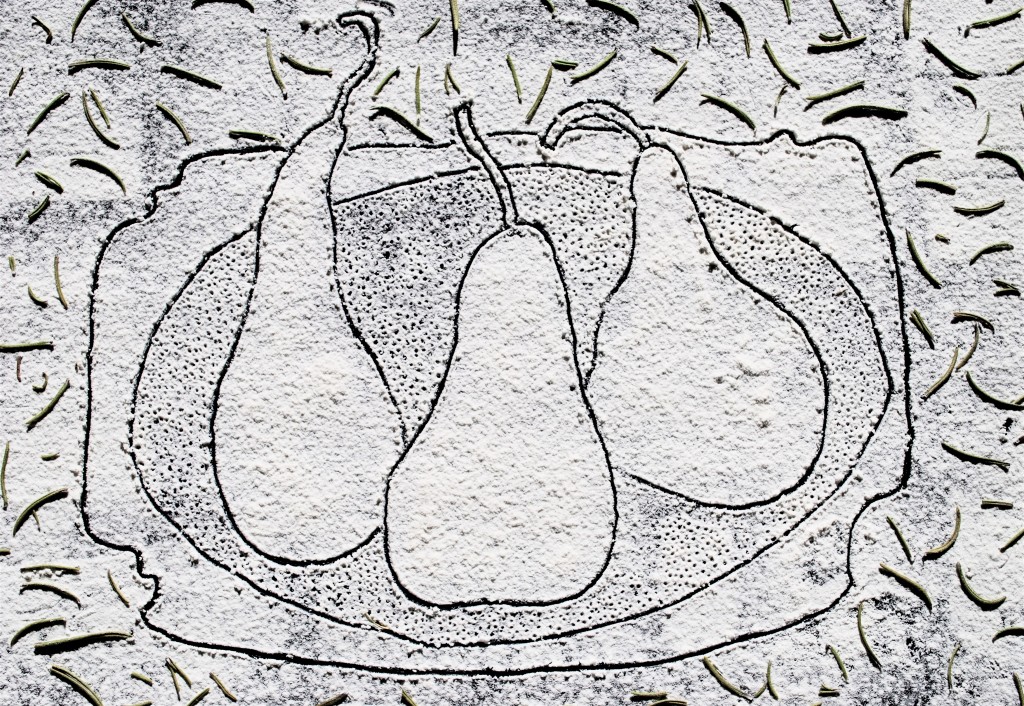

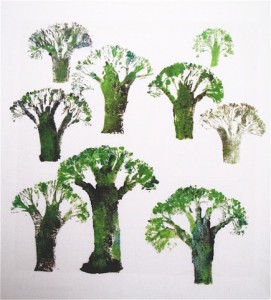

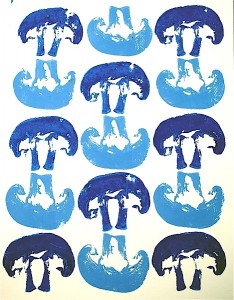

Printing veggies is food for a creative appetite. Head to the market this season for carrots, mushrooms, broccoli, celery, or whatever fresh produce looks good for making a cozy home project or for gift giving. Print veggie images on paper for framing or on ready made fabric items.

Printing veggies is food for a creative appetite. Head to the market this season for carrots, mushrooms, broccoli, celery, or whatever fresh produce looks good for making a cozy home project or for gift giving. Print veggie images on paper for framing or on ready made fabric items.

in the Japanese garden at Georgian Court College, Lakewood, NJ

in the Japanese garden at Georgian Court College, Lakewood, NJ